Book Review 'Indira Gandhi, a life in Nature: How Indira saved Chennai's lung space'

Chennai: In the early 1970s’ Chennai’s lung space encircling the Raj Bhavan complex, widely known as the Guindy deer park, was in danger of being lost to political symbolism and the increasing pressure on urban land for what was being developed as an ‘Institutional Area’ locating a whole array of scientific and technology institutions.

The ‘sprawling’ 555 acres of the ‘beautiful deer sanctuary’ in 1955, was reduced to 330 acres by 1973, “since the state government had merrily been allocating land there to different institutions.” Then Congress MP, Fatehsinghrao Gaekwad, who was president of WWF-Indian arm, had written to the then Tamil Nadu Chief Minister, M Karunanidhi to ensure that at least the 330 acres remained as a “permanent deer sanctuary”.

When Gaekwad wrote to the then Prime Minister, Mrs. Indira Gandhi, to which she replied on December 4, 1973, she had said, “I have spoken to the Governor on more than one occasion, but the Chief Minister has his own views. However, I shall write again.” On the same day, she again wrote to the then Governor, K.K. Shah, seeking his help in “securing a favourable response from the Chief Minister.” Mr. Shah replied ten days later to the Prime Minister stating that Mr. Karunanidhi had assured him that “there was no intention of any further encroachment on the land of the deer sanctuary.”

Years later, in March 1985, when the Union Shipping Ministry wanted to set up the ‘National Institute of Port Management’ near the Adyar estuary in the city, which was opposed by environmental activists, Mrs. Gandhi responded with lightning speed to a message from the noted conservationist Nanditha Krishna, in a move that resulted in the Institute being shifted out of the city to Uthandi and thus the Adyar estuary was saved.

Again in the early days of the Karunanidhi-led DMK government, who was then a keen ally of Mrs. Gandhi, post-historic Congress split in 1969, her prompt intervention ensured that Tamil Nadu did not go ahead with the construction of a 150 mw hydroelectric project on the Moyar river in the Nilgiris that helped to save both the Bandipur and Mudumalai sanctuaries, “rich in elephant herds, spotted deer and sambar; Mudumalai was, in addition, the principal habitat of the Nilgiri gaur (bison),” on representations made by people including Rukmini Devi Arundale and M. Krishnan, the well known naturalist.

The slow firmness with which Mrs. Gandhi staved off the hugely controversial ‘Silent Valley’ project in Kerala in the 1980s’ amid intense lobbying from her own party men, launching ‘Project Tiger’ under her inspiring leadership, saving several birds and animal sanctuaries once the privileged forte of scions of erstwhile Princely States, creating parks and biosphere reserves, enactment of the Wildlife Protection Act, besides clearly setting out India’s stand on environment and development at the “first ever UN Conference on the Human Environment” in Stockholm in June 1972, much before issues of global warming and climate change were raised, are just some of her outstanding initiatives for “ensuring ecological security and sustainability” as India strove for economic growth to fight poverty. It also meant keeping an eye on population growth.

In each of these clusters of positive initiatives, apart from her own passion for knowledge about wildlife, Mrs. Gandhi had never hesitated to consult a wide range of advisers, domain experts, nature lovers, scientists and well-wishers. This list is virtually endless, including both Indians and foreigners, ranging from the great ornithologist Dr Salim Ali, world renowned architect Buckminster Fuller to the late Prof M.G.K Menon.

All these and more, including exchanges with her friends, close aides in Government like P.N. Haksar and Sharada Prasad, flow gently like Tennyson’s Brook in Congress MP Jairam Ramesh’s painstakingly researched book titled, ‘Indira Gandhi, A Life in Nature”.

The author has lucidly prefaced each phase of her environmental concerns with the politico-historical backdrop. Right from Indira’s early days - having to spend lot of time at hill stations due to her mother Kamala’s illness and her days in Tagore’s Shanthiniketan are crucial in that phase - when her father Jawaharlal Nehru was also a teacher amid the jail life during India’s freedom struggle, her ‘Companionship Years’ with Nehru as Prime Minister, her own later years as the head of the government, Jairam Ramesh shows that it was a mosaic of factors that shaped her sensibilities as a nature lover and the need to develop a harmonious relationship with the environment.

It is never easy to integrate environmental planning with economic policies and programmes. But Indira Gandhi, the author says, had a sharp mind for ecological logic, as much as her empathy for nature and environment reflected a lifelong commitment. This profound inner calling of the late Mrs. Gandhi, a little known but a far-reaching catalytic drive to her otherwise decisive and domineering political persona as a Congress leader, had manifested in several decisions, policies and programmes over nearly three decades of her public life to protect the country’s wildlife and ecology.

Thus to read the former Union environment minister’s work on Mrs. Indira Gandhi as a naturalist, as merely paddling along a maze of archival material, besides “unpublished letters, notes, messages and memos” in gently ‘chronicling’ this facet of the late Prime Minister, that had its failures too, would be to miss the woods for the trees.

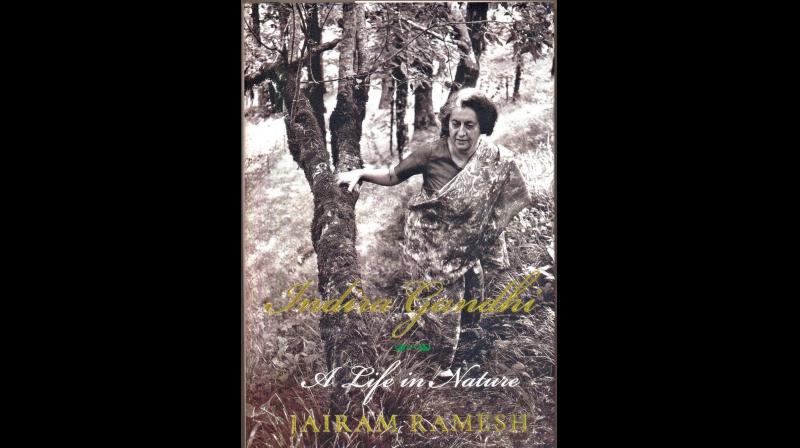

Indeed, Jairam has beautifully structured his narrative, lucidly deconstructing a deeper ethos and teleology that defined Mrs. Gandhi’s approach to nature and environmental issues. He also laces it with his candid criticism of some of her key decisions - like the go-ahead for the Mathura oil refinery close to the Taj Mahal, and the low-grade iron ore mining project in Southern Karnataka. In sum, along with some splendidly rare photographs and uncommon views of Mrs. Gandhi, this work comes as a whiff of fresh air to a richer and subtler understanding of a remarkable woman leader of modern India.